The secretive hard-Left group driving the NHS junior doctors’ strike

Substantial parts of Britain’s oldest trade union are steered by a cabal of activists – and they’re planning a whole new level of disruption

Last year, a young doctor from Sheffield called Jo Sutton-Klein paid her first visit to the London offices of her union, the British Medical Association. “I was quite taken aback at just how fancy they were,” she wrote. “Waitress came to serve us lunch, swish audiovisual set-up. There was a huge sense of detachment from the actual working conditions of junior doctors.”

With its members-only restaurant and lounge, its garden filled with “medicinally significant” plants, its library, courtyard fountain and statues, the BMA’s imposing Lutyens-designed building, in Tavistock Square, feels less a trade union headquarters, more a cross between an elite university and a private club.

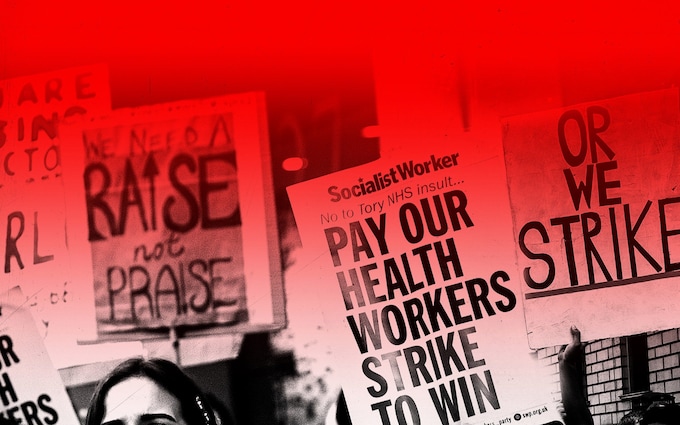

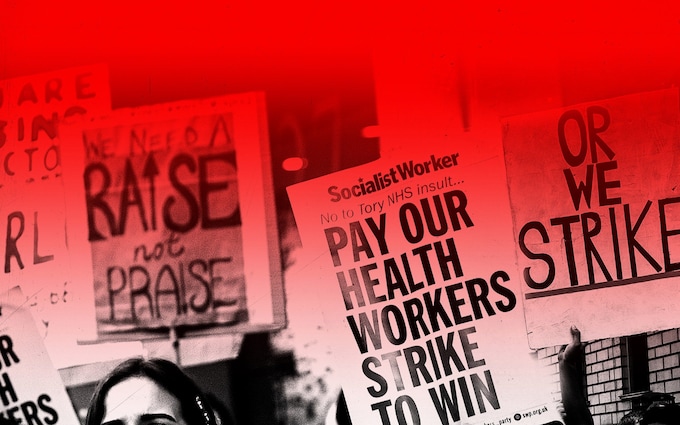

Medical symposia, rather than political rallies, are the usual fare in its grand meeting rooms. As publisher of the British Medical Journal, its main printed output is academic articles on the latest cancer treatment, not angry placards attacking Tory cuts.

But thanks to Sutton-Klein and her allies, all that is about to change. The BMA has just started balloting some 40,000 English junior doctors for perhaps the most aggressive strikes yet proposed – including the full withdrawal of emergency care for three days – in pursuit of up to a 30 per cent pay claim over a period of up to five years.

That is all thanks to the fact that substantial parts of Britain’s oldest trade union have been taken over by a group of young, self-declared “entryists” in a planned campaign similar to that in Labour at the time of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership.

Corbyn is, indeed, directly cited by some of those involved, and key people are former activists in his supporters’ club, Momentum. Sutton-Klein, newly elected to the BMA Council, says she sees the junior doctor dispute as “a hugely important ideological-political moment”, which could “mark a significant step in the reversal of defeats trade unions have faced since the 1980s”. The BMA should, she says, “situate ourselves in a broader workers’ struggle”. Others see organising doctors as “an opening for socialist politics”.

For the think-tank Policy Exchange, I have combed through hundreds of pages of internal documents and online discussions in which the activists reveal their views, tactics and plans. As they say, “never in the history of the BMA has such a large-scale, coordinated effort been made”.

Their methods – an inner core of hard-Left figures (“Broad Left”) within a larger insurgent group (“DoctorsVote”) – will be familiar to students of caucus politics. They now control the BMA’s junior doctors’ committee, which is running the current ballot and proposed strike action; 26 of the 55 voting members on the whole union’s ruling Council; and the deputy leadership of the BMA. “The BMA is no longer the BMA of old. With DoctorsVote comes new management,” the activists promise.

They call themselves “a small group of like-minded people”, but they are secretive, refusing to identify all their leading figures for fear of “government reprisal”. They are a “collective with no single leader”, “mainly” comprised of full-time doctors and controlled by a “steering group”, with both “named and unnamed members”.

Some who we can identify, however, have extreme views, or a record of serious misjudgment. One new Broad Left member of the BMA Council, Becky Acres, has attacked the Labour Party as “proto-fascist” and the Conservatives as “almost genocidal”.

Emma Runswick, the 27-year-old Broad Left, DoctorsVote and former Momentum activist who is now the BMA’s deputy chair, and its main media face of the junior doctors’ dispute, was on the national steering committee of the UK campaign for “zero Covid” – quite possibly, as China is proving, the worst idea in recent medical history.

Their takeover and strike ballot is due partly, of course, to the inflationary squeeze on living standards; and to wide and genuine dissatisfaction in the medical profession. That discontent is rising, reflected in staff survey results and a significant increase in the number of doctors seeking to work abroad.

But it is due also to the constant repetition of misleading claims; and, perhaps above all, to clever organisation. In its internal “campaigning strategy” for the BMA Council, DoctorsVote decided to use the fact that “BMA elections have painfully low turn-out” and was clear that “persuading current voters… shouldn’t be a big focus”.

Instead, the strategy set out plans for what it called “entryism” – for which the dictionary definition is the infiltration of an organisation, such as a trade union or political party, with the intention of subverting its policies or objectives.

As it noted: “We should encourage people to join the BMA for the purpose of voting in this election. This is particularly worth asking first year medical students to do as they have free/low cost BMA membership.” Online, supportive doctors advised that “you can join for one month just to vote and then end your membership”, with others announcing that they had done so.

To choose its candidates, DoctorsVote carried out a “vetting process [which] took place over several weeks… we must elect representatives who will not sell out, who will not falter under media and government pressure”. The DoctorsVote seats were won with just 1,600 votes – less than 1 per cent of the BMA’s total membership. But it was enough.

At the union’s annual conference, six months ago, DoctorsVote boasted that it had “pushed through… by far the most significant change in BMA industrial strategy for a decade”. That strategy has two key prongs. First, the 30 per cent demand over five years, much bigger than by any other major workforce in dispute. And second: proposals for longer, more comprehensive strikes to achieve it than almost anyone else.

Other health workers, nurses and ambulance staff, are typically striking for a day or two at time – and providing emergency cover. But the BMA junior doctors, if they get their ballot mandate, will start with a 72-hour strike, then “potentially... a week”, without any junior doctor emergency care at all in either case.

The union said last week that hospitals could arrange alternative cover, meaning emergency provision would be “no different to any other day”. “To claim that more patients will die during a period of industrial action is dangerous and unfounded”, said Professor Phil Banfield, chair of the BMA council when approached for comment by the Telegraph. “It is within the Government’s gift to avert any strike action by coming to the table and negotiating fair pay for [junior doctors].” In the internal material, however, Acres admitted that “of course… patient safety could be compromised to varying degrees… Unfortunately, a strike has to be disruptive in order to work”.

The last junior doctors’ strikes, in 2016 – which were shorter and mostly didn’t withdraw emergency cover – saw 71 extra hospital deaths, according to a previously unnoticed publication of the BMA. There were six days of strikes, grouped in ones and twos across three-and-a-half months. Emergency care was withdrawn for two of the days.

Furnivall et al, in the British Medical Journal, found there was a 9.75 per cent increase in deaths in A&E units – 31 more deaths – in the strike weeks versus normal weeks, despite a 6.8 per cent fall in A&E attendances.

There was a 1.3 per cent increase in “emergency admission” deaths, or 40 more deaths, emergency inpatients who went on to die in another part of the hospital. That was despite a 3.7 per cent fall in emergency admissions.

The article stated that “mortality did not measurably increase on strike days”, apparently because the authors defined any increase below 5 per cent as not measurable and decided that the 9.75 per cent increase in A&E mortality was on too low a base.

The activists, at least, seem fully prepared for unpopularity. As Sutton-Klein put it, “the only way to win back decent pay is by taking disruptive and lengthy industrial action… for as long as it takes… Things like ‘professionalism’ [and] ‘looking respectable’… are not relevant for trade unions.”

It all started in 2020, with the creation of Broad Left, whose most active members were Runswick and Sutton-Klein. Runswick, who had only graduated the year before, appears to have used her time at medical school as a trial run.

In 2016, she and two other hard-Left activists described how, under the banner of “Labour Left Students for Corbyn”, they “made a successful intervention into Manchester Labour Students, a notoriously Blairite grouping [and]… hotbed of party careerists”, which favoured a “narrow electoralism” rather than “organising alongside workers”.

These efforts led to charges of bullying – “disingenuous” according to Runswick – but she did admit that she and the others “organise[d] caucuses and recruit[ed] heavily… we used our Left caucus as a battering ram to open up an insular Labour club”.

Runswick, who was also active in Momentum, then moved on to the national steering committee of the UK Zero Covid Campaign, which demanded “a full UK-wide lockdown until new cases in the community have been reduced to close to zero”.

At an online campaign rally in November 2020, only three weeks before the first patient received their Covid vaccine, Runswick continued to insist that “the primary measure against this virus is isolation” and criticised the fact that workplaces and schools had reopened “to maintain profits for the ruling class”.

As China has demonstrated, pursuing a zero Covid policy would have been disastrous, imprisoning tens of millions for months longer than necessary, causing greater economic and social harm and resulting in a surge of deaths when the policy inevitably became untenable.

One thing that Runswick doesn’t seem to have done enormous amounts of is working as a junior doctor. She graduated from medical school in 2019, but last year took “time out of [junior doctor] training to locum, so I can do a PGCert [teaching qualification], BSL [British Sign Language] qualification and still have money to enjoy life a little.”

The BMA said last week that the Government’s intransigence meant there was “no option left” but to strike. But Broad Left have been trying to commit the union to strike action and direct attacks on the Conservative Party for almost two years, since long before inflation spiked. Until the sudden arrival of DoctorsVote, they weren’t having much luck with this agenda. At the 2021 junior doctors’ conference, their motion calling for it was defeated.

Speaking against, a former chair of the junior doctors’ committee, Jeeves Wijesuriya, said: “We are currently a non-partisan union. When I was JDC chair in 2016-19 we got £120m in additional [pay] funding and an 8.4 per cent uplift over four years – not by trying to eat an elephant in one go, but by going above employers to a secretary of state that, God forbid, was a Conservative.”

Another speaker, a member of the Labour Party, warned that explicitly party-political attacks would “alienate a significant proportion of our membership”.

A few months after this setback, up popped DoctorsVote, a group that, at least initially, avoided party politics, presenting itself as a simple pay campaign. Not everyone in DoctorsVote is a member of Broad Left. But almost everyone in Broad Left is part of DoctorsVote – what Runswick calls a “Venn diagram” of overlap – and the Broad Left people tend to be the most active.

Away from their doctor-facing statements, the leaders of both groups remain intensely partisan. As Rob Laurenson, the DoctorsVote co-chair of the junior doctors’ committee, put it in October, “doctors are being coerced into the managed decline of our healthcare system by this government. We will not participate in their failed plans.”

Laurenson and his co-chair, Vivek Trivedi, believe that the 2016 strikes failed, as they see it, because “days of action were staggered and made little impact. The answer must be consecutive days of real impact”.

The union has hired a former RMT rail union official, Matt Waddup, to organise the strikes, and says it is training more than 300 junior doctors in campaigning . It has issued an “activists’ guide”, which tells doctors to draw up a “power map” of relationships in each NHS trust and gives them a “messaging triangle” of things to say.

Sutton-Klein has warned that doctors should “anticipate inordinate and aggressive resistance… from capital and its representatives i.e. the government and political class, the media… We should anticipate that those in the BMA bureaucracy who choose to support the campaign will be subjected to media vitriol similar to that faced by Jeremy Corbyn.”

Junior doctors make up only about a quarter of the BMA’s overall membership; most are consultants or GPs. But as the hard Left has grown its control, the union’s public statements have become more partisan and strident. Its strike ballot announcement said ministers “treat the public as fools”; it depicts the Health Secretary, Steve Barclay, as “Wally” from the “Where’s Wally” cartoons. Earlier this month, the BMA’s leader, Phil Banfield, accused the Government of making a “political choice” which caused patients to “die unnecessarily”.

The BMA’s official magazine, The Doctor, devoted much of its December issue to an attack on austerity, which it said had caused 735,000 more working-age people to suffer from multiple serious health conditions during the past two years (the rise was actually due to Covid, and the figure was falling until then).

It attacked the “doubling” of street homelessness between 2013 and 2018, but neglected to mention that it has halved again since. It ended with the story of a man who “tries to pick people up when they are down. After more than a decade of austerity, communities… are asking when, if ever, the government will be minded to do the same”.

What the average junior doctor makes of all this is still to be seen. According to the BMA, 79 per cent of juniors say they “often think about leaving the NHS”, with 40 per cent saying they “will” leave as soon as they find another job. The union claims that junior doctors’ pay has fallen by 26.1 per cent in real terms since 2008.

These figures are exaggerations: the NHS’s 2022 staff survey, with a sample three times the size, finds that 23.8 per cent of junior doctors and dentists often think about leaving the organisation they are currently working for (not the NHS as a whole) and only 10 per cent want to leave the NHS altogether.

The truth about pay is also more nuanced. Average junior doctor pay – currently around £57,000 a year – has fallen in real terms, but not by as much as the BMA claims (they make the calculation bigger by using the discredited Retail Prices Index measure of inflation and taking the wrong pay year).

In the same NHS survey, only a minority – albeit a large one, 39.1 per cent – of junior doctors and dentists were dissatisfied with their pay. That was lower than most other NHS staff, including adult and general nurses (48.2 per cent), nursing auxiliaries and healthcare assistants (59.9 per cent) and ambulance technicians (66.1 per cent).

But this is not to deny two important things. Firstly, that junior doctor unhappiness is undeniably growing – dissatisfaction with pay was 29 per cent in the NHS staff survey of 2019, and only 19 per cent were thinking about leaving.

And secondly, with the increase in inflation and workload, that dissatisfaction has almost certainly grown further since the latest survey was conducted. Last year, almost 7,000 doctors (of all grades) applied for certificates to work abroad, up from 5,500 in 2021.

When the ballot closes next month, Broad Left and DoctorsVote are likely to get their strike. But some older hands at the BMA are worried that the new crowd are riding for a fall with a wider membership that, while angrier than before, may not yet be fully ready for mass confrontation with patients’ lives in play.

At a time when even the Labour Party has accused the BMA of “living on a different planet”, it remains unclear whether junior doctors, only about two-thirds of whom are even in the union, will want to become foot soldiers in the “broader workers’ struggle”.

Andrew Gilligan is senior fellow at Policy Exchange. ‘Professionalism is not relevant: the activists taking over the British Medical Association’ is published next week