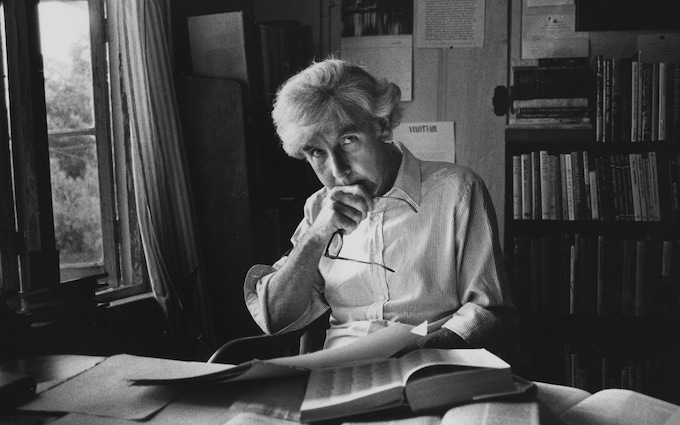

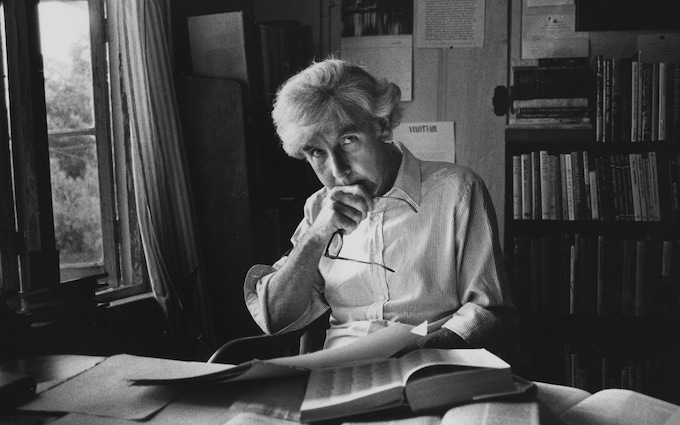

Ronald Blythe, much-loved author celebrated for Akenfield, his classic book about village life in Suffolk – obituary

Blythe conceived Akenfield not as an exposé of rural life but as ‘the poetry of the ordinary’, exploring the rich variety of ordinary lives

Ronald Blythe, the writer who has died aged 100, was best known for Akenfield (1969), a portrait of a remote Suffolk village over the last century, shaped out of the personal stories of its inhabitants; the book won critical acclaim in Britain and America and in 1974 was made into a film by Peter Hall.

Blythe spent the whole of his life in or near Suffolk. Born at Acton, near Lavenham, he lived for most of his adult life in a small farmhouse in the hamlet of Debach, near Ipswich, and later in Wormingford, near Colchester, in a house bequeathed to him by the artist John Nash.

A solitary, shy yet warm man, Ronnie Blythe had a gift for friendship and an enduring fascination with other people’s lives: “I think my view of human life is how brief and curious most people's lives are,” he said. “Yet when you come to talk to them, you realise how strong they are and how unbelievably rich their lives are.”

Blythe got the idea for Akenfield (not the village’s real name: the inspiration was Charlsfield but it was broader than that) when out walking in the countryside: “I walked round the village boundaries which are ancient ditches: very deep, dug into the clay, and full of torrential yellow winter water. And the idea came to me of the fundamental anonymity of most labourers’ lives. In the church at Akenfield there is a long list of names and few remember who they were or what they looked like. Yet they were alive in our own century. So one wonders about the generations before. This is how the book began. A sort of compassion for farming people.”

Blythe conceived his book not as an exposé of rural life with its scandals and secrets but as “the poetry of the ordinary”, exploring the richness and colour in ordinary human lives. He avoided village “characters” who might reinforce rural clichés, but brilliantly conjured up the personalities and manner of speech of the ordinary people of Akenfield.

His cast of characters included the retired colonel who takes on with formidable energy first one derelict farm, then another; the upper middle-class lady magistrate with broadminded views on village incest; the lady Samaritan who keeps the confidence of villagers in distress; the gravedigger with the story of the golf club secretary who wants to be buried facing the links; the orchard foreman describing the lessons that can be learned from apple and pear blossom, and the smith who rarely shoes a horse but is growing rich on “quaint and curly” ornamental ironwork for a new – and despised – breed of rural commuter.

Blythe deflated the idyllic view of the rural past and many of his characters had horrific tales to tell of rural suffering. His district nurse recalled how old people were treated in the early years of the century: “People like to think now that grandfathers and grandmothers had on honoured place in the cottage. In fact, when they got old, they were just neglected, pushed away in corners. I even found them in cupboards. Even in fairly clean respectable houses you often found an old man or woman shoved out of sight in a dark niche.”

Blythe’s skill in persuading people to talk and the sometimes poetic way in which they expressed themselves aroused some suspicions as to the book’s authenticity; some critics suggested he was guilty of putting words into the mouths of his interviewees.

Blythe denied these charges: “When a farmworker said: ‘I have deep lines on my face because I have worked under fierce suns’,” he said, “it certainly was an odd and untypical remark, but it came out of an emotion which our meeting had unwittingly released.”

When Akenfield was published in 1969, it sold well in England where it won the Heinemann award and became an O-Level set book. More surprisingly, it caused a sensation in America where it received enthusiastic reviews in some 150 newspapers and magazines, including Time and Newsweek.

The film and theatre director Peter Hall proposed making it into a film, but at first found it difficult to get financial backing in Britain and was advised to go to America and find “a bankable actor who can speak Suffolk”. Eventually London Weekend Television agreed to help and the film (made with a cast of Suffolk villagers) became the first British-made film ever to open the London Film Festival – in 1975.

Ronald George Blythe was born on November 6 1922, the eldest of six children of Albert and Matilda (née Elkins), and was educated at St Peter’s and St Gregory’s School in Sudbury. As a child he never travelled away from Suffolk and was nine before he knew that places existed that were not near the sea.

Later as an adult he would visit France, and four of his siblings emigrated to Australia, where he visited them. He also lectured in America. But, as he said: “There are people who travel without moving too far.”

His mother was a fundamentalist Christian and under her influence he became a lifelong churchgoer, beginning at Sunday school, becoming a chorister and later serving as a churchwarden and chairman of his local parochial church council.

He discovered literature early on, beginning with the Bible read daily by his mother, and devoured library books. He longed to be a writer, but feared he would not be able to afford the life: “I could not think how to live without any money. Then I met a whole circle of people who also had no money and who were somehow living: WR Rogers, the Irish poet, RN Currey, one of the most distinguished poets of the Second World War, and then John Nash. It was a kind of apprenticeship. We used to drink beer in pubs and talk very seriously about writing.”

After leaving school, Blythe became a reference librarian at Colchester Public Library, and worked there for over a decade. He also began to sell his work: poems, criticisms, essays, and short stories. Eventually he settled in a small house in Debach.

He had his first critical success with A Treasonable Growth (1960), a novel set in pre-war Suffolk, about a local schoolmaster who longs to escape the restrictions of the family home where he still lives, and falls in love with the daughter of an admiral, eight years his senior.

The Age of Illusion (1963) was an anthology of life between the wars which included chapters on subjects as diverse as the life of the notorious rector of Stiffkey and the famous body-line bowling controversy of 1933 .

In The View in Winter (1979) Blythe returned to the documentary style of Akenfield, exploring the subject of very old age by allowing people to talk for themselves. The people who made a success of their later years, he found, were those with a strong spiritual life: “The answer seems to be,” he said, “to preserve one’s spiritual vitality, a vividness and imaginative kind of energy.”

In Divine Landscapes (1986), Blythe explored the places where Britain’s spiritual heritage was born: Bunyan’s Elstow in Bedfordshire, George Herbert’s Bemerton, Langland’s Herefordshire Beacon, and the sites where Cranmer and other Anglican divines were martyred.

Blythe was a long-time friend of the painter John Nash and his wife Christine and as they grew old he became a regular visitor to their house, Bottengoms Farm, near Colchester and would read aloud to them after supper. When Christine died, Nash collapsed and Blythe moved from his own cottage to look after him until his death ten months later in 1977.

Nash bequeathed Blythe his house, garden and cat and Blythe lived there for the remainder of his life, writing longhand and tending the tangled mass of his yeoman’s garden. “I work in my head outside,” he said in 2012. “Doing the tomatoes yesterday, suddenly great big bits of book came into my head.”

Bottengoms was the subject of At the Yeoman's House, published in 2011. Among other books, he published two anthologies of Second World war prose and poetry, Components of the Scene (1966) and Writing in a War (1982) as well as Private Words: Letters and Diaries of the Second World War.

In The Time by the Sea (2013), he revisited his time in the late 1950s when he worked with Benjamin Britten at the composer’s Aldeburgh Festival. It was a picaresque memoir in which he recounted days spent with EM Forster, Imogen Holst, Britten and Peter Pears. “It begins with myself in winter by the North Sea,” stated Blythe. “Shivering.”

From 1993 until 2017 he wrote the Word from Wormingford column for the Church Times: more than a million words of blissful, philosophical prose – both profound and light as air – and these were compiled in Next to Nature, published for his 100th birthday on November 6, and about to be reprinted for the third time. He also reviewed books for The Sunday Telegraph.

Blythe was a member of the Centre of East Anglian Studies at the University of East Anglia from 1972 to 1976 and chairman of the Essex Festival, 1981-83. He was president of the Kilvert Society from 2006 and of the John Clare Society from its foundation in 1981 to 2015; in 2011 he published At Helpston, a collection of essays on the poet. He served at various times on the Eastern Arts Panel and the management committee of the Society of Authors.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1969 and appointed CBE in 2017.

Ronald Blythe, born November 6 1922, died January 14 2023